The presence and impact of organised drug crime pose an increasing threat in East Africa. As this threat evolves, media reporting is a key and necessary source of public information. Yet a number of challenges limit the quantity and quality of media coverage of the topic. This, in turn, limits the pressure that the public can exert on governments to better respond.

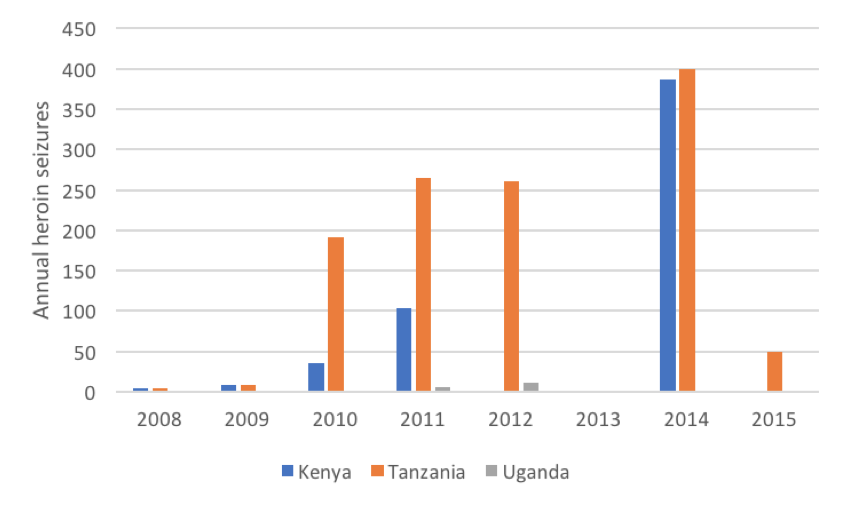

Interviews with local journalists; a review of official seizure data (even if limited); and a systematic monitoring of media coverage of drug-related incidents in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda from 2008 to 2017 (as part of the incident monitoring work of the ENACT project) reveal significant growth in the presence of heroin and cocaine over time – see figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1: Heroin in East Africa – UNODC annual seizure data

Source: UNODC seizure data: annual kilogram amounts of opiod seizures reported, exluding diesel and water-mixed seizures, ‘packages’ and ‘illicit morphine’. No country seizure reports were submitted in 2013.

Figure 2: Heroin-related incidents captured by the ENACT incident monitor

Source: ENACT TOC Incident Monitoring Phase 2 data on Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. The graph only reflects articles and incidents that explicitly mention heroin.

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) World Drugs Report 2017, Europe is the main market for the heroin and cocaine that travel from Central and East Asia, and Latin America, respectively, across the continent through West and East Africa.

However, as the UNODC reports, the trade of heroin through Nairobi, Mombasa, Entebbe and Dar es Salaam has brought about a spike in local use. According to 2015 price estimates, the substance is the cheapest in Kenya, in the range of 500 to 600 Kenyan schillings (around US$5-6) per gram.

Current figures on the scale of rising local use are difficult to come by. In 2013, the World Health Organization reported that there were between 25 000 and 40 000 heroin users in Tanzania; and an estimated 18 000 in Kenya in 2011.

Today’s levels are likely far higher, given that global production rates of heroin rose significantly in 2014, as did East Africa’s role in the global trafficking. With growing use comes an increase in HIV. In 2017, Kenya’s National AIDS and STIs Control Programme estimated that 3.8% of new HIV infections are caused by intravenous drug use.

In response to growing heroin addiction rates, Tanzania launched a national methadone programme in 2011, followed by Kenya in 2012. In Uganda, drug addiction and HIV support programmes remain the work of a select few NGOs. Despite progress, heroin users across all three countries remain stigmatised and in need of far greater support.

Another grave impact of the lucrative trade is the corruption it brings among government officials across all levels; from law enforcement agents at ports and border crossings, right up to senior politicians. Political figures are frequently implicated in drug trafficking across Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania.

The media certainly plays a role exposing the involvement of East African government officials. Capacity constraints and journalists’ fear of reprisals however mean that reporting on drug trafficking is often limited to small-scale seizures and possession incidents.

Access to media also impacts the extent of public knowledge on drug trafficking. East Africans consume the news through three key media types: radio, print and television. Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania each have dozens of daily and weekly newspapers. These are increasingly accessed online and on mobile phones, given the rapid development of broadband Internet and related technologies in the region.

With an estimated Internet penetration rate of 43.5%, Kenya is the most connected country in the region, followed by Uganda at 19.2% and Tanzania at 7.4%. Afrobarometer Round 7 survey results indicate that in 2016, about 30% of Kenyans obtained news from the Internet on a regular basis (between once a day to monthly), compared to around half of this amount in Uganda. (Tanzania’s 2016 results are not yet available.)

Yet despite these advances, radio remains the most popular means to obtain news across the region, whose populations are largely rural. World Bank data shows that the average percentage of the total population that is rural across Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania is 74%, and public perception data shows that East Africa has some of the highest levels of radio use on the continent.

While Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda all have relatively high level of access to media on the continent, the quality of local reporting is limited by capacity and resource constraints of major media houses. These constraints hamper the production of deep investigative journalism, the kind that is necessary to get at the heart of the impact of drugs and the key actors involved.

Journalists interviewed for this article often spoke of going out-of-pocket to cover the stories that took them beyond political topics, or across borders.

Freedom from political interference is another challenge that journalists frequently encounter, and is linked to drug-related corruption. The media in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda are each ranked ‘partly free’ by the 2016 Freedom House Press index. The lack of complete media freedom is evidenced by arbitrary arrests, intimidation and violence against journalists, and the bribing of editors and owners of the media companies meant to expose corruption.

A report by the Committee to Protect Journalists highlighted the incidents of physical violence and intimidation faced by Kenyan journalists following the contested election of 2017. In January of this year, a number of non-state TV channels were taken off air during opposition leader Raila Odinga’s swore himself in as ‘the people’s president’.

In Uganda, a social media blackout was experienced following the elections of 2016. According to reports by Amnesty International and Reporters without Borders, journalists who expose state corruption continue to face threats such as abduction and intimidation in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania.

Capacity constraints and fear of reprisal means that journalists are often unable to tell the full story of drug trafficking in their countries, for instance in exposing the scale of the money involved, how and where the trade crosses borders and revealing high-profile actors involved in the activities.

As a result, regional responses remain focused on drug users rather than actors higher in the trafficking chain. Drug abuse is also surrounded by stigma, which undermines sufficient awareness of the public health crisis that heroin has created across coastal East Africa. The ability of the media to serve as a much-needed watchdog is therefore thwarted, keeping locals in the dark about the scale of the problem, and reducing pressure on governments to prioritise the issue.

In order to break this cycle, media houses need independence from political interference, protection from reprisals and resources to allow for rigorous investigative journalism. Journalists should also consider, where feasible, seeking anonymous publication on independent blogs and alternative media organisations to bypass the financial constraints and interference from potentially compromised media houses.

ENACT hosts training workshops for investigative journalists around the continent. The last two were held in Kampala and Dakar. The full report of the ENACT incident monitoring research on drug crimes in East Africa will be published in May 2018.

Ciara Aucoin, senior research consultant, ENACT, ISS