Tensions are rising in southern Libya’s Fezzan region, after six years of relative stability since the Benghazi-based Libyan Arab Armed Force (LAAF) takeover. This was after nearly a decade of clashes between tribal armed groups, terrorism, foreign rebel forces and illicit markets in arms, drugs, people and fuel.

However, at the beginning of 2025, the LAAF dissolved the 128 Brigade, one of the main fighting forces in Fezzan, to rein in the political and security influence of the commander, Hassan al-Zadma, and his broader Awlad Suleiman tribe (which is one of the most important in the south).

This triggered clashes in February in the Gatrun area between the LAAF and members of a Chadian mercenary unit linked to the 128 Brigade, and further fighting in the Kilinje goldfields nine days later. Though both clashes were short-lived, tension and instability continue.

Despite an LAAF deployment of new units to the area to assert control, intermittent, low-level clashes persist. There has also been an uptick in the targeting for arrest of influential tribal figures and foreigners, particularly those involved in illicit economies.

Together, these events have disrupted the interlinked political, tribal and criminal ecosystems in the Fezzan, and there’s little to suggest that these shocks will drive a substantial shift in the LAAF’s control over the Fezzan.

However, in recent Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime research, interviewees said the greatest impact to date was in the functioning of the regional criminal ecosystem, both reshaping it and driving new actors into it.

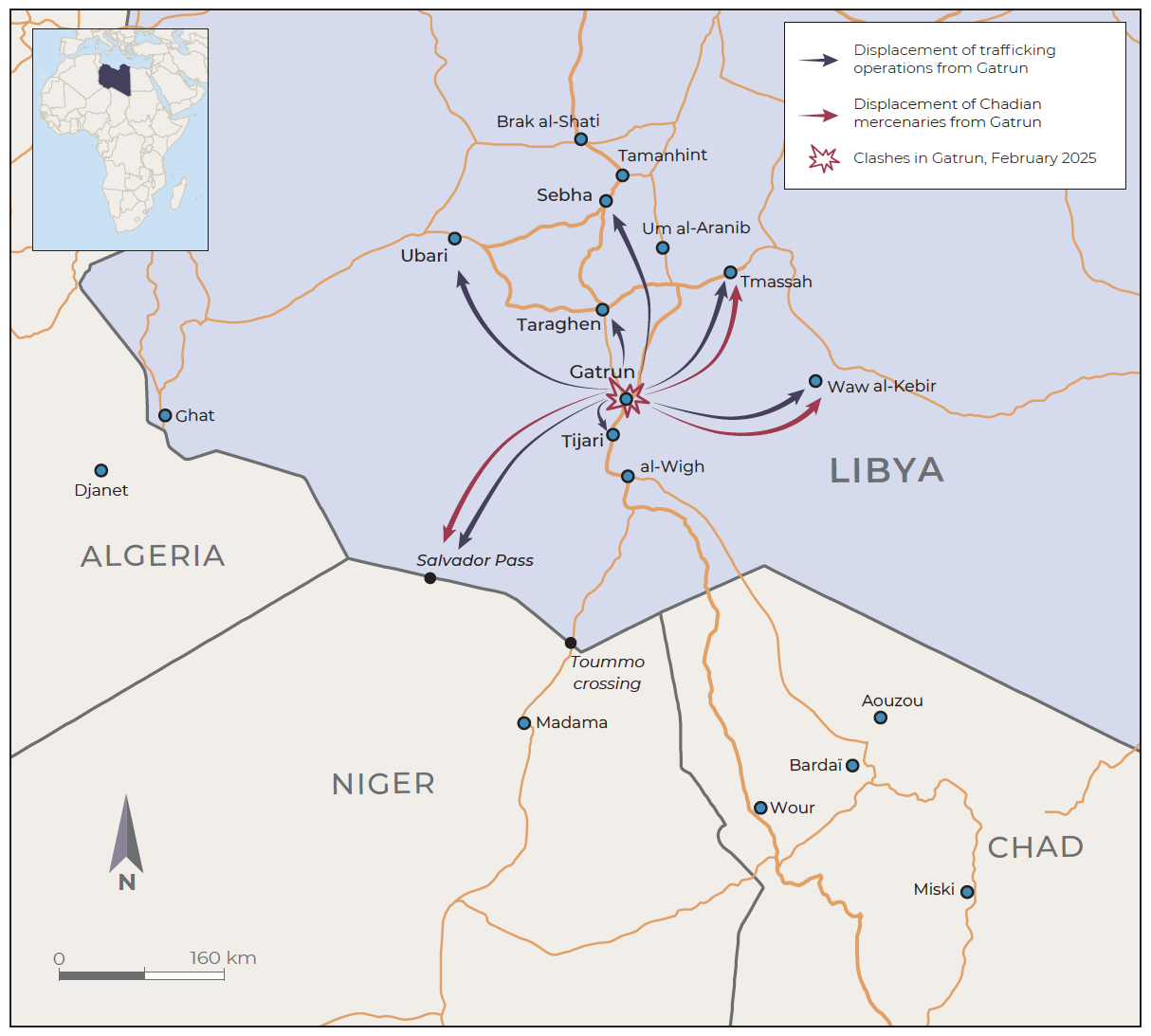

The reshaping of the ecosystem was driven partly by the displacement of numerous important criminal actors from Gatrun, previously an important hub in regional criminality. This was due both to the association of some key criminal actors with Chadian mercenaries involved in the clashes, and the broader crackdown by the LAAF on foreign-linked actors.

Criminal actors shifted their operations either to other towns in southern Libya, like Ubari, Tijari, Taraghen, Sebha, and more remote locations further east – or to Salvador Pass along the Algeria-Niger-Libya border.

One source said: ‘The absence of these [people] in Gatrun, especially those involved in arms and drug trafficking, has had a huge impact on the trade of illicit goods in the town.’

This has impacted other areas in southern Libya – one interviewee noting a shortage and price increase in Moroccan hashish, which had previously been inexpensive and easily available. However, this shift does not mean a permanent disruption in trafficking, but rather the reshaping of criminal economies as networks adapt their operations.

Further, the fighting and subsequent LAAF crackdown led to a near immediate shutdown in some key cross-border markets, including human and fuel smuggling. In mid-February, smugglers transporting migrants north from Agadez, for example, were forced to stop before reaching the Libyan border, leaving over 500 people stranded in Niger, some for several weeks.

Stranded migrants faced harsh conditions, including lack of adequate shelter, food and water, while waiting for their journeys to resume. Some were abandoned by their smugglers and had to fund their own journey back to Agadez.

Similarly, southbound fuel smuggling destined for Niger and Chad was halted, driving fuel shortages in some artisanal gold mining areas and small towns in northern Niger that depend on contraband petrol from Libya.

By mid-March, the cross-border smuggling of migrants had restarted, though at a lower level than before. Most smugglers, however, shifted their routes to bypass Gatrun and LAAF checkpoints on the border, or adopted techniques such as night-time travel without lights to avoid patrols. Despite this, as of June, the number of migrants transported per week was roughly half that recorded in January.

The impact on fuel smuggling has been equally persistent, with high prices and shortages recorded across northern Niger and Chad. While this links partly to issues in smuggling fuel, sourcing challenges have also crept in, with the LAAF reportedly closing private fuel stations across southern Libya, leaving only a handful of public stations open. One source said queues could last up to 48 hours, with prohibitions on fillings canisters.

The shortages have had a knock-on effect on illicit economies. One smuggler in Agadez noted people were exiting human smuggling because fuel was expensive. Other interviewees said bandits were increasingly targeting the limited number of remaining fuel smuggling convoys, largely to source petrol for their vehicles and continue operations.

In turn, as illicit economies have been reshaped, new actors have been driven into them. Most Chadian mercenaries who fought in Gatrun fled the town, relocating to northern Niger and areas around the Salvador Pass, a key border artery for illicit trafficking. Other Chadian mercenary groups, based in Gatrun but not involved in the clashes, also fled the town to areas of southern Libya such as Tmassah and Waw al Kabir. They have continued trafficking from there.

The Salvador Pass relocation is notable. It has increasingly emerged as a refuge for former mercenaries and armed group actors forced out of southern Libya. They use the pass as a base for trafficking activities and for banditry targeting smugglers and traffickers, leveraging the weapons, vehicles and experience accrued from their LAAF service.

The Gatrun crackdown has pushed numerous drug and arms trafficking routes into areas in northern Niger close to the Pass, creating heightened predation opportunities for ex-mercenaries.

Whether intentional or inadvertent, the LAAF appear to have altered the criminal status quo in Fezzan in a way that is surprisingly durable. The long-term implications are unclear. However, there are some dynamics that could worsen instability and criminality risks in the region and should be tracked closely.

First, the relationship between smugglers and the LAAF has become oppositional in a way it previously was not. For much of the past five years, the LAAF strategically instrumentalised illicit markets as a tool of rule, tacitly allowing local armed groups and fighters to continue contraband activities or receipt of bribes from smugglers to head off unrest or opposition to the LAAF. The shift in the relationship, if sustained, will likely limit such profiteering.

While positive from a rule-of-law perspective, such a limitation could nonetheless heighten discontent and tensions among LAAF-affiliated groups in the Fezzan that have come to rely on such funds.

Second, this also has implications for the LAAF’s relations with local communal actors. Allowing continued smuggling by local groups mollified opposition to the LAAF’s control of the area. This is more than simply a matter of armed group profiteering – smuggling is a critical economic livelihood for local communities in southern Libya. Any action against it heightens social pressures by community members on the armed groups linked to them and on the LAAF.

Continued constriction of the illicit economy could further heighten broader tensions among key tribes in Fezzan against LAAF rule. This risks a feedback loop, with heightened tensions furthering efforts by the LAAF to assert control, which impacts illicit economies and drives more unrest.

Finally, the rising number of heavily armed actors, including bandits and current or former mercenaries, in the Libya-Niger-Chad borderlands, poses a distinct stability risk for all three countries. They represent a pool of former fighters who have the weaponry and experience to threaten regional military units. In southern Libya, while some mercenary groups retain links to the LAAF, the Gatrun clashes have shown that such relations can deteriorate rapidly and risk instability.

If tensions continue to rise in southern Libya and fighting occurs, this could expand, with mercenaries and fighters either hired back into conflict, or drawn in by grievances against the LAAF. As one Nigerien smuggler noted: ‘All it takes is for someone to hide away with weapons in order to stir up trouble.’

Matt Herbert, Head of Research: North Africa and the Sahel, GI-TOC, and Alice Fereday, Senior Analyst, GI-TOC

Image: Eric Lafforgue/Art in All of Us/Corbis via Getty Images