For Africa to deal with organised crime, it needs the right laws in place, and the skills and political will to enforce these laws. Although imperfect, the UN Convention against Transnational Organised Crime (UNTOC) provides a global framework for what countries’ organised crime laws should look like. But is the framework being used in Africa, and what does this mean for effective responses?

The UNTOC has received a fair amount of criticism. Viewed by some as a relic of an outdated notion of organised crime – the convention has been accused of failing to keep up with new and emerging threats, and avoiding defining ‘organised crime’ altogether.

Despite its shortcomings, the UNTOC does provide a starting point for states to translate their international commitments into national contexts. One key feature of the convention is its emphasis on international cooperation; an essential element for states in their practical response to organised crime, which so often transcends borders. Moreover, while failing to define ‘organised crime’ in and of itself, the UNTOC does, notably, offer definitions for an ‘organised criminal group’ and ‘serious crime’.

At the very least, these terms provide states with basic parameters and the flexibility to address the widest possible range of concerns. For example, how the convention defines ‘organised criminal group’ allows for broad applicability, recognising that criminal associations can range from hierarchal structures to loosely connected networks. Its focus on profit-driven activities also allows for laws to distinguish organised crime from activities that are politically motivated, such as terrorism.

Likewise, the ‘serious offence’ criterion ensures that national legislation directs focus away from low-level criminality. In other words, these definitions offer a sort of ‘common denominator’ to the myriad of organised crime activities, providing tangible guidance for state implementation.

At the time the UNTOC came into force, organised crime was not high on the list of priorities for Africa, and African states played a limited role in the finalisation of the convention. Today, however, the UNTOC has been ratified by the majority of African states (52 out of 54 countries – Somalia and South Sudan being the two outstanding states) – with most doing so immediately after the Treaty was concluded in 2000.

The act of ratifying is, however, only a first step towards the implementation of an international instrument. Depending on countries’ individual legal systems, international standards lack force until incorporated into national legislation. Once incorporated, states propel international obligations towards practical application by adapting them to their specific needs, legal traditions and social, economic, cultural and geographic conditions.

While the UNTOC remains the major international legal instrument on organised crime, its relevance depends on the extent of its implementation. Until recently, due to both technical and arguably political reasons, the UNTOC had no framework to measure the level of states’ compliance with the convention.

Last month, however, the Conference of the Parties to the UNTOC finally established a review mechanism. This allows for an appraisal of countries’ performance in meeting their obligations under the convention, through encouraged dialogue with non-state actors and submissions of an initial self-assessment and desk-based peer reviews. While the establishment of the mechanism symbolises a huge step forward in the practical implementation of the UNTOC, it is notable that no African states (other than South Africa, to a limited degree), were actively involved in the negotiations – not unlike during the inception of the convention itself.

As part of the development of the ENACT programme’s Organised Crime Index Tool, which measures states’ relationship with organised crime, we have sifted through hundreds of national laws, in their native language, to determine whether they meet a series of both general and crime-specific guidelines. Specifically, we assessed how many organised crime laws African countries have and which types of organised crimes are criminalised.

It should be noted that while the UNTOC is widely regarded as the main international instrument in the fight against organised crime, it is by no means the only one. Several crime-specific instruments, such as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, and the Convention against the Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, provide particular frameworks for their respective criminal markets. With this in mind, we provided an additional limited analysis of ‘general organised crime’ laws (as opposed to criminal market-specific legislation) to determine whether criminalisation in these laws meets the ‘serious’ offence provision outlined in UNTOC; and whether these laws criminalise ‘organised criminal group’ as defined by the convention.

As a basic premise, only national legislation was considered, and laws had to actually criminalise a specified type of organised crime, distinguishing such offences from ‘regular’ crimes. Taking a broad, inclusive approach, states were given the benefit of the doubt and given credit for laws that covered organised crime activities even if they were not transnational in nature.

All relevant independent laws, criminal code provisions and substantive amendments were included, while laws that focused only on corruption and predicate or inchoate offenses were not considered. Research was undertaken without regard to time period, due to the relatively static nature of legislation. In other words, in order to account for the spectrum of legislative systems across the continent, if a law could apply, it was included.

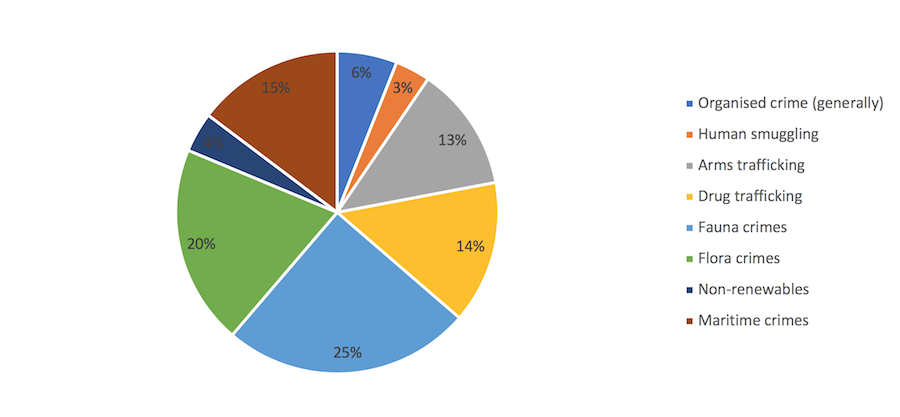

Based on a search of publicly available sources, we found 354 relevant laws (excluding human trafficking) across 54 countries in Africa. Bearing in mind that many laws cover more than one crime type, some 129 laws or provisions focused on fauna crimes (wildlife trafficking) across the continent, followed by flora crimes (104), maritime crimes (76), drug trafficking (74) and arms trafficking (65). This is in contrast to a mere 31 laws or provisions on ‘organised crime’ generally, and only 21 and 18 laws or provisions on non-renewable crimes (i.e. the illicit trade of oil, diamonds, gemstones and gold) and human smuggling respectively.

Figure 1: Percentage breakdown of all laws / provisions by criminal market

So, bearing in mind the limitations of open source research, what can be inferred from these results? Of course, not every country in Africa is afflicted equally with every type of organised crime. At the same time, there is a clear emphasis (or lack thereof) on certain types of organised crime. This clearly reflects priorities on the continent, but also poses a problem if other types of organised criminal markets are known to be present.

So, bearing in mind the limitations of open source research, what can be inferred from these results? Of course, not every country in Africa is afflicted equally with every type of organised crime. At the same time, there is a clear emphasis (or lack thereof) on certain types of organised crime. This clearly reflects priorities on the continent, but also poses a problem if other types of organised criminal markets are known to be present.

With regards to the convention, all ‘general organised crime’ laws met the UNTOC provisions on serious crimes and organised criminal groups to some degree: some 20 out of 54 countries have passed legislation that meets both of the convention’s definitions. Unfortunately, a mere 25 countries have such laws in the first place.

Figure 2: Presence of UNTOC definitions [%breakdown of laws/provisions by criminal markets]

Interestingly, keeping in mind that many criminal markets are covered by other international instruments, many countries with market-specific laws/provisions also had the two UNTOC features present. For example, even though human smuggling had the fewest related laws or provisions on the continent, 41% of countries (seven out 17 countries) with related laws complied with the two UNTOC standards.

On first glance, it seems that while Africa has little problem in developing organised crime legislation, these laws fall short of meeting the UNTOC considerations. Crime type-specific legislation is particularly lacking in meeting these definitions, compared to their ‘general organised crime’ law counterparts. On the other hand, criminal market-specific laws/provisions don’t necessarily need to achieve that if they fall under the purview of other market-focused international instruments.

Where do we go from here? Even if African countries were to amend their laws to meet UNTOC definitions, would this mean that the continent has taken care of its organised crime problem? Clearly not. Legislative incorporation is just a small step towards the implementation of effective responses to organised crime. Nevertheless, it’s a step in the right direction, towards a more unified legislative framework.

African lawmakers should tackle organised crime legislation from two angles: first, by amending existing laws to better adhere to international criteria; and secondly by passing more general organised crime laws to cover any crime types not addressed by market-specific legislation.

Laura Adal, Senior Analyst, The Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime