It takes millions of years for sand to form in waterways – but just hours to strip and send it along an illegal chain of trade that is costing Kenya millions of shillings in lost revenue annually. Run by violent criminal cartels, this trade is destroying local livelihoods and the environment, as well as increasing conflict in the communities living in sand-producing areas, an ENACT study shows.

This precious commodity is sourced locally in most of Kenya’s semi-rural counties in the east, west, central and coastal parts where informality and lawlessness reign. The chain of activity is mostly covert, and there isn’t much support to resolve the tensions or advocate against the actors.

After water, sand is the most used natural resource in the world. In Kenya it is used for both macro and micro construction. This includes big government infrastructure projects such as berths in seaports, and smaller civil builds such as real estate.

While sand is a renewable resource it needs to be harvested rather than mined. Harvesting is carefully regulated to ensure sustainability as it conforms to the extraction of sand up to certain levels and in ways that allow the resource to replenish itself naturally. Sand mining, on the other hand, involves the complete removal of sand from the source. Criminals extract sand up to bedrock level by, for example, driving trucks into waterways and mining riverbank s, eliminating the prospects for replenishment.

Before 2007 there was no sand extraction regulation in Kenya, and criminals took advantage of this regulatory gap to broker the mining and trading of sand through a cartel system. In 2007, the first regulation to govern sand activities, which included the harvesting and trading of sand, was enacted. However, this regulation was not implemented by government.

With the change of Kenya’s constitution in 2010, county governments were mandated to develop and implement policies on natural resources and environmental conservation. Out of the 47 county governments though, only Makueni has put in place a framework of such policies and an authority on sand harvesting.

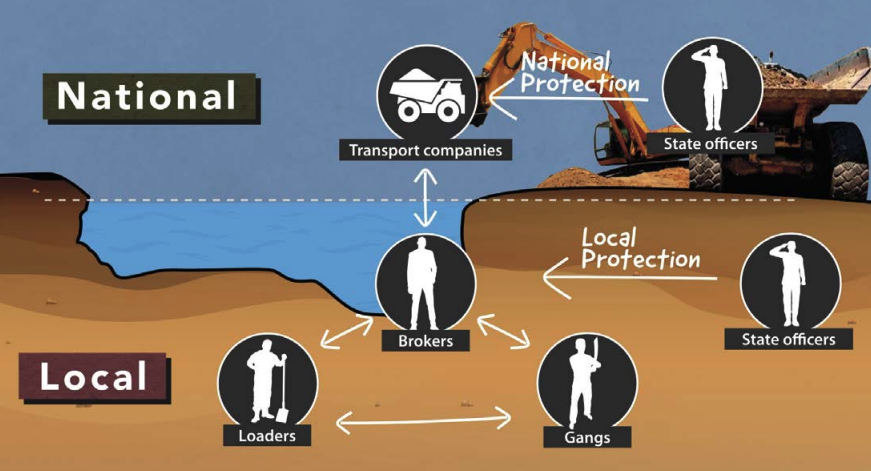

Despite the regulations, cartels illegally mining sand in Kenya include brokers, loaders and gangs who operate at local levels where the sand is sourced. Transport companies use brokers to source sand locally. Loaders fill sand trucks for the brokers, while gangs offer protection and prevent conflict with local communities or other cartels.

State officers are integral to this illicit trade, working together with the transport companies that sell the sand to the end user. For a fee they protect the cartels so the criminal value chain can operate with impunity.

|

Chart 1: Key actors in sand trafficking in Kenya

Source: ENACT research paper: Kenya’s sand cartels: Ecosystems, lives and livelihoods lost (click on the chart for the full size image) |

The ENACT sand study sampled four counties in Kenya: Machakos, Kajiado, Nairobi and Makueni. The findings reveal that up to 500 overloaded 10-tonne sand-tipper trucks leave Machakos during the day, with up to 200 leaving Kajiado. This number doesn’t include those travelling at night. The main market for this sand is Nairobi City County where the demand for construction is the highest in the country.

This unregulated and illegal mining is damaging the environment, the study shows. The destruction of sand ecosystems has a multiplier effect on waterways and land surfaces. Such destruction leads to the loss of birds and animals that live or depend on water bodies. Trees and other vegetation whither and, over time, this environmental degradation makes the land unproductive for farming – a subsistence livelihood practice that local communities depend on.

People’s lives are also affected as communities are divided, with those in favour of sand mining as a source of income and those against it due to the negative consequences. This dilemma increases community tensions, leading to sand-related violence and even deaths.

Those who support the illegal sand mining feel they are entitled to the resource and see it as a godsend that will pull them out of poverty and hopelessness. Some women with no other sources of income have been indirectly driven into commercial sex work to serve the sand workers at the mining sites.

Children are also used for labour in sand mining. During the COVID-19 pandemic, when schools were closed for long periods, opening only erratically, more children became involved. It provided them with a daily income. With the pandemic subsiding, schools have reopened. But parents are struggling to get their children back to school as they want to continue earning, says Jacob Maluki of Kenya’s Water Resources Authority.

Sand mining in Kenya is a crime that must be stopped urgently. Since sand is a local resource and the first casualties of this crime are the communities in the sand-producing areas. It is at this level that solutions must be developed, with responses tailored by communities living in sand-producing areas, as the case of Makueni county has indicated.

Makueni is the only county in Kenya with a framework to guide its sand activities. Once an epicentre of sand mining, the county established several laws and a central sand authority to regulate sand harvesting and trading in 2015. In seven years, Makueni has managed to weed out the cartels and replenish sand on its land surfaces and in waterways. The county now has enough sand for commercial trading and is planning to set up centres where ethical trading of sand can commence.

Looking further afield, there are no regional frameworks from bodies such as the East African Community or the African Union to regulate sand activities. There are also no international frameworks on sand extraction activities. At present, the United Nations (UN) Environment Programme guidelines and the upcoming UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) guide to good legislative practices in responding to illegal metals and minerals mining and trafficking could steer regional and national initiatives. ENACT is part of the review panel on the UNODC draft, which has provisions for anti-child labour and exploitation.

However, these regional and national frameworks can only be applied effectively if national efforts proactively include responses from the local levels in sand-producing areas. Community voices are critical in informing inter-local policies and thus national frameworks to regulate sand activities, as the case of Makueni demonstrates.

Mohamed Daghar, Regional Coordinator, Eastern Africa, ENACT Project, ISS